It has been interesting to read the first posts on Dracula - they express a variety of responses, all valid, and often perceptive.

As JH's journal continues into the later chapters, the drip feed of information continues; slowly he uncovers the stereotype of a vampire that we, as modern audience recognise: no reflection, staying up all night, the sudden lust for fresh blood, the repelling power of the crucifix. And, despite ourselves, the terror that grows within him is effective in arousing our own tension - he is prisoner, and trapped by the count, with no feasible means of escape.

The Count's voice is an interesting one to track - he is dominant yet polite. He knows he has the upper hand, and allows this to be known, but is never really aggressive to JH. He 'allows' him to leave, albeit when the wolves are baying at the door, and indeed, protects him from the vampire women. There is thus a dual layer of interaction: the veneer of courtesy and polite conversation, and yet, under the surface (and seen only from JH's perspective) this restriction and fear seethes. Would this be an effective coursework topic? Dracula's perspective of events? How would he see it differently from JH? How much sympathy can we really show him? There is that interaction with the women where they say 'you yourself never loved'... Dracula denies this... so what's the story there? Another interesting backstory waiting for the telling...

How about these women? Are we on more familiar ground here? We have discussed bloodlust in class: where better to find it than this particular chapter? The description of the women's approach to Harker's neck is undeniably sensual. But how is this effect created?

First, look at the repetition of comparative adjectives: ' lower and lower went her head'; 'nearer - nearer' and then the verb - summarising the drawn-out pace of the paragraph - 'waited - waited with beating heart'.

Then, look at word classes - are there patterns? Well, yes. The nouns focus on body parts: 'lips', 'lips', 'tongue', 'teeth', 'lips', 'breath', 'neck', 'skin', 'throat', 'flesh', 'hand', 'lips', 'skin' and then...'teeth'! Look how 'lips' are repeated! The adjectives in the paragraph add to the sensuality: 'thrilling', 'scarlet', 'red', 'hot', 'soft, shivering [touch]', 'supersensitive', 'languorous' 'beating [heart]'.

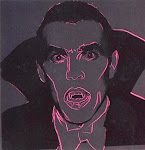

What a change then, just as JH succumbs to their presence - he is saved by the Count in all his demonic glory - 'fury','rage','passion'. 'His eyes were positively blazing. The red light in them was lurid, as if the flames of hell-fire blazed behind them. His face was deathly pale, and the lines of it were hard like drawn wire; the thick eyebrows that met over the nose now seemed like a heaving bar of white-hot metal.' The overwhelming image here? FIRE - and not just a little one - but the fire of hell itself.

Contrast these images then with JH's grotesque discovery in Chapter 4 - 'swollen', 'bloated', 'gorged', 'like a filthy leech'. But what is the greatest horror? Not that which can be seen. No - for JH the greatest horror is worse than a visual image: it is the thought that he has played a part in assisting Dracula - the very thought 'drove me mad'.

So we leave Jonathan, as Dracula leaves for London, planning his escape down the castle walls... next stop Mina's letters - a new voice, a new location, new concerns...